After going into the details of the book Bastard Culture! – How User Participation Transforms Cultural Production by Mirko Tobias Schäfer (he published it in 2011), I knew that I had to invite Mirko to take part at the conference MutaMorphosis – Tribute to Uncertainty in Prague last December under the topic of “Limits of Collaboration” as an already accepted panel suggestion. Beside artistic and curatorial approaches I wanted to bring in a critical approach on a broader level when it comes to the topic of the so-called social media structures that we (in Europe and the western world more or less) are all in. How are we intentionally or unintentionally, voluntarily or involuntarily learning and perceiving interaction, communication, participation in a digital culture that is mainly characterized by re-using existing software and interfaces that are already developed and provided and lead us into the paths of guided participation? In addition Mirko was questioning social platforms as emerging public spheres that are pretending to be oriented toward the public’s interest while corporately owned and being geared to economics.

Praising Participatory Culture, Limiting User Agency (revised transcription of his talk on December 7, 2012, at the conference MUTAMORPHOSES – Tribute to Uncertainty, Prague, Czech Republic)

Mirko Tobias Schäfer (DE/NL)

This is not a presentation on Facebook, although I will refer frequently to examples taken from Facebook, since it is a handy tool to point out specific mechanisms that are implemented in social media platforms to make users do what they do when using web applications.

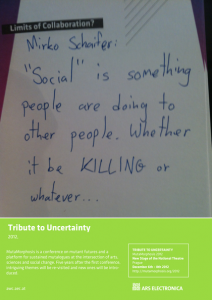

But before we start let me focus on participation a little bit. With the term ‘participation’, new media are framed as emancipating users and enabling them to do things that they were not able to do earlier. I do not fully agree with that, and I have written a book to deconstruct this popular notion of participatory culture and new media. What I try to do is to step back and find a non-normative description and definition of participation. I identified participation as a great legend of social interaction and cultural production online that is contributing widely to the general understanding of what we now call social media. And I could also add that the word ‘social’ in social media is already problematic, since it is framed in the popular discourse as something that a cosy, friendly community does together. But we know that social just means that people are doing something to people, which could also be killing each other or whatsoever.

What I found interesting about investigating participation and interactions of users online is actually that there are two forms of participation: implicit participation and explicit participation. Explicit participation describes user activities people refer to when speaking about participatory culture. Here users are working consciously in a community or team to achieve common objectives; they participate explicitly. Fan culture as analysed by Henry Jenkins represents prominently explicit participation, online activism and online communities are also examples of explicit participation. Implicit participation describes activities users are not always consciously aware of, since they are guided through the interface design. A good example for implicit participation is Google’s ReCAPTCHA, where users type over a two word phrase from a small image presented to authorize access to whatever kind of service. Simultaneously they help Google to read passages from scanned-in texts, that the machine can’t read. And simply through using platforms such as Twitter, YouTube or Facebook, or services such as Google and Amazon, users already create value and they even actively contribute to the improvement of services and information management. However, they are most likely unaware of their participation as it unfolds implicitly. I recognized that implicit participation is far more interesting than explicit participation because it enables the platform providers to make people do things they are not fully aware of and help them participate, or to take part in actions without making a big effort. I consider design features for implicit participation crucial factors for the success of the popular social media platforms.

Implicit participation implements user activities subtle into software design. Think of the popular social media applications and their easy to use interfaces. Their most persuasive features are ReTweet, RePin, Favourite, Like or Endorse buttons. Producing content is not difficult on these platforms and that is – as I will show later – a key factor within the cultural production logic of these platforms.

These companies have understood user activities that have been unfolding online since the web became a pervasive tool in the mid-nineties: activities, such as posting content online, having conversations, reaching out to people, sharing private thoughts and experiences, documenting their personal everyday life, commenting on other users productions, etc. They implemented those activities in easy-to-use interfaces and developed business models to monetize them. Consequently, user activities were employed for various purposes from information management to harvesting data for targeted advertising. Think of Flickr, which uses the meta-tags users add to photos for improving the Yahoo search engine’s image search. Through easy-to-use interfaces, the threshold of interacting with other users and simply using web applications has been significantly lowered. This is a key aspect of the popular web applications. But to succeed commercially they need a large user base. The easier an interface is to use, the easier it is to create content, even if you are not actively creating content (users ‘create’ through simply multiplying or reproducing content). This is an important feature for those platforms. It leads to the increase of user numbers, and those increasing user numbers make the platform attractive for venture capital. That is why this is a “winner-take-all economy“ in fact.

Since participation has become a mere commodity. Therefore it is important to emphasize the ambiguity of participation. Those companies go out of their way to point out that participating on their platforms is actually something like joining a community. However, the community aspect, which we know from the nineties, when people were really interacting with each other online, has been now implemented as a mere option. Users can use many of these platforms without actively reaching out to other users and those platforms will still work fine. The self-organization of communities that we know from the nineties has been consequently rendered irrelevant on commercial platforms. It has made room for a tight, top-down management by the platform providers. The user interfaces and the back-end design allow platform providers to channel user activities, monitor what users are doing, and stimulate users to do something they do not mind doing and are actually not really aware of. The most important thing for platform providers is limiting the uncertainty of having large user numbers who could do whatever they might come up with. In order to remain advertiser and third-party friendly, the masses of users need to be channelled and their self-organization potential needs to be tamed.

I would like to guide you briefly through some examples to support my argument. I will discuss a choice of user interface examples taken from Facebook. We can see the over-emphasizing of participation on Facebook’s government page. In 2009 Mark Zuckerberg addressed his community of Facebook users in a very interesting pose, in shirt and tie and not in the stereotypical uniform of a nerd programmer: the t-shirt. He more or less imitated the official format of a presidential address note. He also emphasized in his speech that Facebook, if it were a country, would be the largest in the world. By providing this video message in the various languages Facebook offers its services in, he is also addressing a multi-national plurality of ‘citizens’. Zuckerberg calls the users of Facebook to participate in a vote. It is very interesting that the company is framing the terms of use and the end-user license agreement as something debatable which would be open for discussion. The reality shows that it is actually not. The emerging governance, as I would like to call it, is very much visible on the Facebook government site. Users actually have to ‘like’ it to receive updates about it, and only if one hits the like button – just think of this symbolic notion that you have to ‘like’ the government’s communication channel – she will be invited to participate in the votes. The recent vote has been opened to all users of Facebook. In an e-mail invitation, Zuckerberg calls users to vote. Actually, for those who are not aware of it, one proposal that the users are voting on is abolishing voting on Facebook, because Facebook wants “to create a more meaningful way” of gathering user feedback. Apparently, user participation in decision making processes is explicitly not a meaningful process for Facebook.

Another aspect we have to consider is that providing a platform becomes an inherently political business. This becomes not only visible in the rhetoric of user deliberation and participation, but also in providing a platform for communicating corporate decisions as policy decisions. In case of Facebook they are presented as if users would have participated in the processes of decision making, which is evidently not true. Facebook’s Governance Page serves as such a communication feature. Google uses the Google Public Governance Blog and almost all of the other popular web platforms have some interfaces to address their users and communicate their policies to them.

The aim of these features is to establish a notion of legitimacy. Here we have Zuckerberg stating, “Overall I think we have a good history of providing transparency and controlling over who can see your information.” But also we know that Facebook is regularly violating privacy laws, for instance in Germany. Despite repeatedly addressed concerns, German law enforcement is not really actively concerned about those issues. A few months ago the ‘governor of Facebook’ posted to his personal page that he celebrates the fact he has 1 billion users a month. As any good politician would do it, he framed by saying “I am committed to working everyday to make Facebook better for you, and hopefully together one day we will be able to connect the rest of the world too.” These are just a few examples, there are many more which are similar. They support my argument that the community aspect, the participatory culture aspect is emphasized as the ‘legend’ of social media while it has actually been formalized in software.

In terms of the graphic user interface we see many strategies that are used to channel user activities. I will point out only two, but we could go through many features on all other platforms as well. One point is blocking of certain hyperlinks. Facebook is known for blocking links that lead to either spam or files that might infringe copyrights. The Facebook Like button is very interesting example: it is a very effective feature to make people communicate and interact. And there are good reasons why there is no Dislike button, though there are many petitions on Facebook demanding one. First of all Facebook, as an advertiser friendly platform, is made solely for commercial uses. And no big company would like to see dislike buttons referring to their brand. The philosopher Andrew Feenberg noted that “Technological design is the key to cultural power”, and we can see perfectly how interface design is actually shaping culture and shaping the way people can interact with each other.

Another feature we could look at is the comment function in Facebook service updates. It does not invite discussion or debate. Its design fundamentally different from the old newsgroup format where we find these long, at times exhausting discussions in which people quote each other at length to refer to what they have said earlier or where they refer to extensive quotes from other sources that touch upon the current debate. The Facebook status updates are actually not suited for that, as there is one overriding interest in an uncontroversial platform: it has to be an advertiser friendly platform and it needs to be easy to consume. The design favours ephemeral forms of communication. Indicating affection, approval, sympathy not by explicitly stating it but through hitting a like button, adding an emoticon or an abbreviation as ‘lol’ or ‘rofl’.

Another thing I am just starting to realize is how these brief responses, the use of Likes, ReTweets, Favorites, views etc. fuels interaction on social media platforms. I think they work like a currency. They are like ‘small change’ that makes it possible for users to get in touch without actually communicating with each other. Awarding someone a Favorite, is really easy, easier than posting a comment. And the interface design supports it. This actually fuels interaction among people on social media platforms, because it is so easy and persuasive to indicate affirmation through an interface feature. Many people on Flickr seek to receive many ‘Views’ for the photographs they upload, the same is true for videos on YouTube. Many people on Twitter love to receive favourites. As my colleague Johannes Paßmann notes, there is a huge, vivid scene on Twitter which exclusively revolves around this aspect of Twitter Favorites.

These are the important elements for lowering the threshold of participation. Instead of writing a comment or reacting to something, I just have to like or favourite it. It is much easier than coming up with short sentence. This additional lowering of the threshold invites even more people to participate.

LinkedIn had none of these features for a long time. It provided the opportunity to write recommendations. That would work, if recommendations are answered in kind and the author would also receive recommendations. However, it seems the feature was not used widely. The bar for writing a proper recommendation is quite high. LinkedIn therefore found a way to lower the threshold for recommendations by introducing the ‘Endorsement’ feature. Now users can simply click on a button to endorse skills of their fellow network members. When using LinkedIn, the interface displays at a point skills of fellow users with the invitation to endorse them. An ‘Endorse all’ button makes it very easy to be generous with endorsements. And indeed, they seem pervasive – like an inflation. Because it is so easy to give them away. You can endorse four people at one time. And they will endorse you back. It fuels the interaction of users and pushes profiles into the news timeline in LinkedIn (which is very similar to a Twitter timeline).

Another aspect that is interesting about the back-end of social media applications is that they are made for market research through evaluation of user data. The back-end design provides great means of control, although control might too harsh a word, transparency of user activities and user relations might be more apt, but it is also exploitable for control. There are great evaluation tools available to see what people do online. And it serves solely monetizing user activities and is actually the reason why these platforms exist. Through an Application Programming Interface third parties of social media platforms gain access to user conversations and data about user activities. Some companies are excplitily proud of “listening into their customers’ conversations”. Gatorade sports a Gatorade Social Media Mission Control Center. And Dell uses the Dell Social Media Listening Post, which actually resembles a kind of secret service facility where spys wire-tap your conversations. And actually, this is what they are doing. They want to know who is talking where with whom about which aspects of the brand or product and whether this information can help them to improve it. But actually they are considering to manipulate the conversations by improving what people say about their brands. Manipulating public opinion online is only a continuation of traditional PR business in social media, since it is what PR has been doing successfully in mainstream media for a long time.

Prior to the social media monitoring for marketing and market research purposes another form of monitoring takes place. Social media platform providers employ extensive content moderation services. Recently the content moderation guidelines for Facebook were leaked onto the internet. The manual reveals that the company is less concerned about spam, less concerned about broken skulls, but very much concerned about naked breasts. Nudity is something that has to be removed from Facebook, because they want to remain an advertiser and family friendly platform.

There are companies specialized in online content moderation work, which contradicts our understanding of “user generated content”. This content is actually always the result of a co-production process by the content moderators and the content reviewers and not the users’ original activity alone. Everything that appears on these platforms is reviewed and monitored through tools that were set up earlier and are normally not identified. Certainly we have automated content review filters, like software filters on YouTube that automatically scan the audio tracks of a file to match it with a huge database of copyrighted material. And very interestingly, we have, similar to the distributed Favorites and Likes, a distributed form of content review through ‘flag’ and ‘report’. Not only in endorsing content the threshold has been lowered, but also in reporting allegedly inappropriate content, the interface provides a most convenient way to do so. Users can indicate by simply clicking on ‘Flag’ and ‘Report’ that content appears to be inappropriate or offensive. Often, this is content just does not fit their own world-view and they flag and report it in a way of personal censorship. On YouTube for instance, it is really interesting to see the war that goes on between atheists and hardcore Christians and how they use all the means YouTube offers to flag their opponent’s content for removal.

Facebook’s system of controlling users and channelling their activities finds an equivalent in the way they control their shareholders. They use a dual class shareholder policy, which means that there are Class A shares and Class B shares. Class B shares are more powerful. So, although Zuckerberg himself owns only 28% of the stocks in his company, he controls 57.1% of the voting power because his Class B shares are more equal than other shares.

Why am I concerned about this? I would not care about it if Facebook, Twitter or YouTube were simply shopping malls where people go once in a while, do some shopping there, and then leave again to go on with their everyday lives. But user practice indicates that the social media platforms have emerged as something else. They constitute something that I would call – with reference to Stefan Münker – an “emerging public sphere”, something that blends into the existing public spheres and our everyday life. These platforms provide an additional space where we do things that we know from our traditional way of forming opinions, speaking about politics, and sharing information. I do not buy into the idea of the Twitter revolution or Facebook revolution; I just want to indicate that user practice indicates – apart from all the nonsense and superfluous private stuff unfolding on these platforms – that they are also spaces for discussing politics, raising issues, and being critical, forming opinions, very similar to activities in public space, although these online spaces are corporately owned and governed. Users are at times dissatisfied with the corporate rules and are participating in all kinds of petitions, protests and demonstrations to win the ear and the consent of platform providers. They have even formulated a Bill of Rights for social media in the hope that platform providers recognize them as ‘citizens’ and grant cultural and political freedom. We can see artists trying to appropriate the technology – think of the Social Media Suicide Machine – or they provide alternatives such as Thimbl, an open source and non-commercial microblogging service. However, those activities are unlikely to affect the dominant platforms as long as they keep their user base.

The commercial platforms are powerful and attract attention. Politicians are seeking collaboration explicitly, as they are interested in how those platforms work. Discussing social media platforms and how they blend into our everyday life addresses three notions of politics.

1. Politics-of-platforms, the governance designed by the platform providers.

2. Politics-on-platforms, the debates unfolding among users, and also debates users initiate to discuss politics.

3. We have something I would for the time being label platforms-in-politics, dynamics where the platform providers mingle with the policymakers.

The latter manifests in cooperation of policymakers and leading internet corporations in conceiving the policies for governing the internet and the regulation of user activities. During the e-G8 summit in Paris Zuckerberg and other industry leaders were invited to speak with the mighty and powerful, while the civil society was actually excluded. Lawrence Lessing was invited as a representative of civil society, but he was denied to use the opportunity for informal chats with politicians which was naturally granted to industry leaders.

An EU funded research project on the social impact of ICT, for which I served as an external reviewer, found that the main motive for government and public administrations – who have started experimenting with e-participation – is simply to close the gap that is perceived to be growing between governments and citizens and to boost the legitimacy of government policy and administrative decisions. Politicians do not really have an interest in citizen participation just as social media platform providers do not want their users to participate. But both politicians and platform providers employ participation as a rhetoric means to pretend legitimacy.

Facebook represents itself to users as a sort of legitimate governor, as an entity that has sovereignty and the legitimacy to enforce guidelines of use and social interaction, not based on their corporate power (which would be appropriate) but founded in a deliberation process of users, backed by a community of users who agree to the agreed upon the terms of use in a deliberative process (which is not true). Facebook tries to obscure the fact that they own a platform and are dictating tools for interaction and cultural production as well as the terms of use. I would have no problems with that if it were not part of public space, but it is now increasingly becoming public space. It is therefore necessary to think about how power will be distributed in those hybrid public spheres. We need to discuss whether corporate social platforms are suited for expanding public space. I am thinking not only about Facebook, but also the extent to which cultural heritage institutions are currently very eager to transfer our cultural resources to corporate platforms in the desperate hope of finding more or new audiences. I have no issues with the corporations; I have an issue with conflicts of interests, especially if this conflict of interest clashes with the public’s interest. Society needs to be defended in the view of an ongoing commodification of public administration and public space.